|

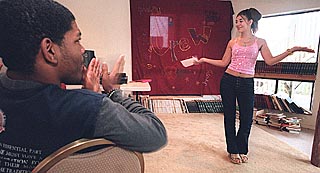

| Eleventh-grade student Jayna Fortson gives a book report in front of her English class while 10th-grader Dharma Shay shows his approval at the Waters of Life charter school in Puna.

Deborah Booker • The Honolulu Advertiser |

Freedom to educate without the red tape Freedom to educate without the red tape

A close-up look at Hawai'i's present and future charter schools A close-up look at Hawai'i's present and future charter schools

By Alice Keesing

Advertiser Education Writer

PUNA, Hawai‘i — Every school day, about 50 students make the long trip down a washed-out gravel road to a two-story house where they take classes in the converted garage or an upstairs bedroom. It’s unconventional and crowded but, for many, this is the first time they’ve enjoyed school.

The name of their school is Waters of Life. And it’s that name that eventually surfaces as lawmakers and Board of Education members voice their apprehensions about charter schools. They worry about health and safety at Waters of Life’s three sites: the makeshift additions, the crowded rooms, the adequacy of the kitchen and bathrooms.

Waters of Life staff make no bones about the fact that they’re different. That’s the whole point of charter schools, they say.

"This doesn’t look different from charter schools all over the nation," said Waters of Life co-director Truitt White. "They started in houses, in tents, on reserves. It may look different ... but it doesn’t really lack what the students need."

|

| In charter school Waters of Life, classes are conducted in rooms of a converted house in Puna.

Deborah Booker • The Honolulu Advertiser |

Nevertheless, Waters of Life is under the scrutiny of local and state authorities for violating building and health codes. Hawai‘i County has given the school until Sunday to get the correct use permit for the properties, or face fines or closure. The health department also is investigating the schools’ bathroom and kitchen facilities.

In addition, House Education Chairman Ken Ito and Board of Education Chairman Herb Watanabe visited the Waters of Life elementary school in Nanawele and came away worried.

"There are about 40 kids in the elementary school — and this is a private home — there were about 10 or 12 kids in the living room with no furniture, sitting on the floor with no cushions," Watanabe said.

White said the school is constantly striving to upgrade facilities and he worries the clampdown may force Waters of Life to close its doors.

"We’ve been told by our board members and parents they want us here," White said. "They say we need to have some education in this area."

Moving to an area with the correct buildings and zonings would take the school away from the community that needs it, he said.

Last hope for some

The mission of charter schools goes beyond teaching children to read and write, according to Libby Oshiyama, president of the Hawai‘i Association of Charter Schools. As at other charter schools, Waters of Life staff often drop off and pick up students for the school day, help with family problems, make sure they have food to eat and a safe place to stay.

Charter schools are the last hope for some children who don’t learn well in a traditional classroom, Oshiyama said.

Charter schools promise to bring choice and innovation to a public school system that many feel is failing Hawai‘i’s children. Yet those who are fighting to get them off the ground are finding the way as bumpy as the gravel road that leads to Waters of Life.

A 1999 law paved the way for 25 charter schools in Hawai‘i, which is one of the last states to join the reform movement. Perhaps best described as an independent public school, charters aim to increase parent involvement, experiment with different learning styles and bring more choice to the public education system. Six charters are now operating in Hawai‘i. Five more have been approved for the coming school year and even more are lined up waiting for approval.

‘Month of craziness’

But over the past month, their future has been unclear, with indications that some want to hit the brakes on the movement. There have been questions about the cost and the accountability of the new schools. And charter advocates say they’re being wrapped in the red tape and bureaucracy they were created to escape.

Oshiyama describes recent events as "a month of craziness."

"The magnifying glass is so hot our backs are peeling," she said. "The scrutiny is enormous."

|

| Students Santino Caralallo, left, and Pertrum Pe‘a prepare apples for other students at Waters of Life.

Deborah Booker • The Honolulu Advertiser |

Oshiyama and others have spent the past weeks fending off a flurry of bills that they say would have been the death of charter schools.

"If those schools fail, we don’t need the Board of Education or legislators to tell us because the parents will just walk away," Oshiyama said. "That kind of accountability is much faster, more deadly than anything you can legislate."

Arguments like that helped convince Senate Education Chairman Norman Sakamoto to kill a bill supported by the governor that would have revoked all new charters in 2005. And they persuaded Ito out of a bill that would have imposed a moratorium on the grant-

ing of any more charters. Instead, Ito said, participants will sit down this summer to see if they can work out the problems.

But the Board of Education, which has the authority to grant charters, has its share of worries, too, and tension has developed between it and charter supporters as they try to find the line between charter independence and board oversight.

Negative vibes

Some question how appropriate it is for the board to be Hawai‘i’s chartering agency.

"Charter schools were invoked everywhere because of dissatisfaction with the way boards govern public schools," said Mary Anne Raywid, a national expert in school reform. "Board members are the natural enemies of charter schools, so whatever they say is going to be predictably negative."

And some believe the board didn’t prepare for the advent of charters after the bill was signed two years ago.

"They haven’t been proactive, they haven’t been out there to assist and now they’re looking at this like it’s Pandora’s box," said Lanikai Elementary Principal Donna Estomago.

Frustrating process

Board members, in turn, have expressed their own frustrations, saying they anticipated the problems and wanted more time to resolve them before the governor signed the charter bill into law.

Instead, they were left holding a reform movement for which no extra money was provided and over which they have no control. With no power to turn away a complete application, board members say they are merely acting as a rubber stamp.

Concerned about liability, the board earlier this month turned back an applicant, saying it now will require everyone to prove they have met codes, including building, health and fire, before they get their charter.

That puts applicants in a Catch-22, Oshiyama said.

"They can’t get their lease without a charter, and now they can’t get a charter without a lease," she said.

However, board members say they are not trying to stop the reform movement. They constantly reiterate their support of the concept and say they will do whatever they can to help applicants through the process.

But for Keikialoha Kekipi, the new requirements mean he probably won’t be able to open his school in Puna for "at-risk" students this fall.

"What is worth more? The structure? Or the education?" he asked. "We need these grassroots schools to take care of the lives of these people and we’re being stifled."

Contradicting costs

And then there is the question of money. The board was alarmed to hear from the department last year that staff for the new charter schools would cost as much as $6.8 million. Schools chief Paul LeMahieu said he doesn’t want that money to come from existing public schools, however, the governor did not include any additional money in his budget.

Charter advocates question that amount and insist they are not a financial burden on the state. With their flexibility and freedom from bureaucracy, they say they can operate for less money than regular public schools.

"There is the continuing myth that we are draining money," Keola Nakanishi of Halau Ku Mana charter school recently told legislators. "We are the bargain of the century for the state of Hawai‘i."

LeMahieu, whom charter advocates have counted as a strong supporter, anticipates much more discussion on charters before this legislative session is over.

"This is a hot topic," he said.

Where ever those discussions lead, the supporters of charters vow to continue the fight.

Waters of Life parent Debra DeCosta said she would "do anything short of laying down and dying" to keep the school going. DeCosta drives three of her nine children 45 minutes every day to get to Waters Of Life.

"They want to come to school every day, so I know they’re doing something right," she said.

The road may be rough, but it’s one that DeCosta and others are determined to travel.

[back to top] |